Tuesday, September 30, 2008

Saturday, September 27, 2008

Budweiser American Ale

I saw that Budweiser's Ale was in the singles cooler tonight while I was stopping off for some beer on my way home from work. I felt obligated to at least try it and not just assume that it is going to suck just because it is an Anheiser-Busch product. After spending over an hour trying to figure out how to put my Ctrl button back on my laptop I popped open the Budweiser American Ale and gave it a go. It pours a crystal clear deep amber color with little head retention. It claims that it is brewed with Cascade hops but I wonder how much and when in the boil. I don't pick up that Cascade aroma at all. I get more of a perfumey herbal-type hop aroma and very little. It tastes like mostly pilsner malt bill with some mid-range to darker crystal malt. Leaves a little bit of caramel/toffee notes on the finish. The mouthfeel is pretty lacking, similar to a regular budweiser. Drinkability is pretty good of you like the flavor of it. I don't care so much for how it tastes so I probably won't ever buy it again but if I had a bunch of it lying around I could probably drink alot of these. No suprise. I guess it is a good stepping stone beer for a lot of the light lager drinkers who want to venture into the world of ales. I like the packaging and it even has a pry-off cap!

My gripe is that the label reads:

GENUINE

Budweiser American Ale defines a new style of ale--The American Ale--created by Anheiser-Busch brewmasters to deliver robust ale taste that's full bodied, but not too heavy nor too bitter.

Apparently they just defined American Ale. I would not use "Robust" or "Full-bodied" as descriptors for this beer what so ever. I would describe this beer as carefully crafted in the same manner in which you choose what album to play when your grandparents are visiting.

Friday, September 26, 2008

Sometimes My Job Can Suck

Here's the scoop. We have a new show at the station that I work at and it requires a person to sit at the news desk and run the prompter for the first part of the show because the Anchor who normally runs their own prompter is standing in front of a television screen away from the desk. When you run the teleprompter you have to look right into one of our cameras and read the prompter off of the screen. Well, I was running the prompter and looking into the camera and low and behold the director punched me up in the big TV behind the Anchor while he was talking about a murder suspect. Lucky me. Right before she put me in the monitor whe said "wouldn't it be funny if I accidentally punched up Brian in the monitor" and oi la, there I was.

I would just like to state one last time, I AM NOT A MURDERER

No Cider Mills in the U.P.

Sept. 23, 2008 -- Trapped inside a Lebanese weevil covered in ancient Burmese amber, a tiny colony of bacteria and yeast has lain dormant for up to 45 million years. A decade ago Raul Cano, now a scientist at the California Polytechnic State University, drilled a tiny hole into the amber and extracted more than 2,000 different kinds of microscopic creatures.

Activating the ancient yeast, Cano now brews barrels (not bottles) of pale ale and German wheat beer through the Fossil Fuels Brewing Company.

"You can always buy brewing yeast, and your product will be based on the brewmaster's recipes," said Cano. "Our yeast has a double angle: We have yeast no one else has and our own beer recipes."

The beer has received good reviews at the Russian River Beer Festival and from other reviewers. The Oakland Tribune beer critic, William Brand, says the beer has "a wierd spiciness at the finish," and The Washington Post said the beer was "smooth and spicy."

Part of that taste comes from the yeast's unique metabolism. "The ancient yeast is restricted to a narrow band of carbohydrates, unlike more modern yeasts, which can consume just about any kind of sugar," said Cano.

Eventually the yeast will likely evolve the ability to eat other sugars, which could change the taste of the beer. Cano plans to keep a batch of the original yeast to keep the beer true to form.If this has a ring of deju-vu, it could be because Cano's amber-drilling technique is the same one popularized in the movie Jurassic Park, where scientists extracted ancient dinosaur DNA from the bellies of blood-sucking insects trapped in fossilized tree sap.

Cano's original goal was to find ancient microscopic creatures that might have some kind of medical value, particularly pharmaceutical drugs.

While that particular avenue of research didn't yield significant results, the larger question of how microscopic creatures survived for millions of years could help scientists understand certain diseases, said Charles Greenblatt, a scientist at Hebrew University in Jerusalem who studies ancient bacteria.

"We've got cases of guys who contracted [tuberculosis] during World War II and lived with it for 60, 70 years," said Greenblatt. "Then suddenly they get another disease, the TB wakes up from its dormancy and kills them."

Inducing dormancy could be a new way to fight disease and infection, said Greenblatt. Instead of outright killing infectious creatures, doctors could instead put them to sleep. The infection would still be present in the patient's body, but it wouldn't hurt the patient.

Neither Cano nor Greenblatt can say what the upper limit for hibernating yeast or bacteria is; it could be hundreds of million years. But while other scientists work on that, Cano plans to spend his time tossing back a few cold ones, and hoping others will too.

"We think that people will drink one beer out of curiosity," said Cano. "But if the beer doesn't taste good no one will drink a second."

Related Links:

Thursday, September 25, 2008

Porter...This Is Your Life

Oh Porter, let me count the ways. As a style I give you a 10. The BJCP went as so far to give you a 12. (Categories 12A, 12B, & 12C that is) I'm going to start doing little write ups on things that I find interesting about each beer style. I am going to keep them in order with my homebrew clubs "Style Night" meetings. Our first club "Style Night" is going to be Porter so I am doing what my wise cousin does when she wants to solidify information in the ol' noggin. Write it down, and then write it down even neater and OCD-like, and then high-lite the ever-so-important parts. Well, actually I'm just going to do some research, take some sloppy notes, then blog it out here. First off, let me state that if you are a homebrewer and you are looking for a book that will truly make you a better homebrewer, I highly recommend picking up "Designing Great Beer" by Ray Daniels. I went nuts on Amazon a while back and I bought every book that was respectable by the homebrew community and when I received my box in the mail full of beer know-how I was so excited until I opened this book and I realized, I don't know shit about beer. I thought I was going to sit down and just read through this book front to back and oi la, brewmaster. Not the case. Instead I would just pull this book out from time to time and go to the index and see what it had to say about certain beer styles. Well now this book is probably my favorite book to read that gets me ready to brew. It really breaks down beer styles so you understand where/how they came about, how do other people brew them successfully, what do you need to do to get your beer NHC worthy. I'm going to be using this book for all of my clubs style nights to get more familiar with some of the historical aspects of particular styles as well as how the styles have evolved into today's commercial and homebrewed examples.

Oh Porter, let me count the ways. As a style I give you a 10. The BJCP went as so far to give you a 12. (Categories 12A, 12B, & 12C that is) I'm going to start doing little write ups on things that I find interesting about each beer style. I am going to keep them in order with my homebrew clubs "Style Night" meetings. Our first club "Style Night" is going to be Porter so I am doing what my wise cousin does when she wants to solidify information in the ol' noggin. Write it down, and then write it down even neater and OCD-like, and then high-lite the ever-so-important parts. Well, actually I'm just going to do some research, take some sloppy notes, then blog it out here. First off, let me state that if you are a homebrewer and you are looking for a book that will truly make you a better homebrewer, I highly recommend picking up "Designing Great Beer" by Ray Daniels. I went nuts on Amazon a while back and I bought every book that was respectable by the homebrew community and when I received my box in the mail full of beer know-how I was so excited until I opened this book and I realized, I don't know shit about beer. I thought I was going to sit down and just read through this book front to back and oi la, brewmaster. Not the case. Instead I would just pull this book out from time to time and go to the index and see what it had to say about certain beer styles. Well now this book is probably my favorite book to read that gets me ready to brew. It really breaks down beer styles so you understand where/how they came about, how do other people brew them successfully, what do you need to do to get your beer NHC worthy. I'm going to be using this book for all of my clubs style nights to get more familiar with some of the historical aspects of particular styles as well as how the styles have evolved into today's commercial and homebrewed examples.Some interesting things about Porter:

- "Porter was truly the first "industrial" beer. Rather than being a natural product of the brewing ingredients, it was "engineered" to meet specific consumer needs. (quote from "Designing Great Beers" by Ray Daniels)

- Multiple accounts agree that the year 1722 was the first year that Porter was brewed. George Harwood of Shoreditch Brewery is credited with first brewing Porter by some but it is more likely that multiple brewers started brewing it in the same year.

- Porter came about by patrons requesting the publicans for a blend of different beers. Usually a Mild (young) beer and stale beer mixed or any but not limited to the following combinations. Ale, mild beer, and stale blended. /Half-and half (half ale and half two pennys), /Three threads (Ale, beer, and two pennys),/ Mixture of two brown beers, one stale, one mild. /Three threads pale ale, new brown ale, and stale brown ale./ Four threads and six threads (constituents not given).

- The Labouring people, Porters, etc. experienced its wholesomeness and utility, they assumed to themselves the use thereof, from whence it was called Porter or Entire Butt.

- Original Porter was made exclusively with Brown malt which was kilned over an open fire so one could imagine that there was probably an underlying smokey flavor to these beers. Brown malt was sometimes referred to as "Porter malt".

- Once Porter was established as a style in the 18th century there was a higher demand for it which lead to breweries building large vats for storage and aging of the beer. These vessels where so big that you could hold a dinner dance accommodating 200 people inside of them. (for real, they used to have dinner dances in these motha's)

- October 16, 1822: a vat of Porter ruptured, releasing a jet of porter that first wiped out an adjacent tank and then ravaged the surrounding neighborhood in a five-block radius. At least eight people (including women and children were killed immediately, and a dozen others succumbed to injuries or were crushed by the crowds seeking to consume the fine Porter that was running in the streets.

- Once industrialized, Porter was blended with 1/3 volume of stale porter that was always kept on hand to help bring young porter forward in flavor.

- Taxation put economic pressure on brewers to reduce the amount of malt in their beers. This had an affect on the color of the beer so brewers would used burnt amounts of sugar or molasses to compensate.

- Brewers looked to find other ingredients to use in their beer that would have a stimulating or narcotizing effect that would give the consumer the impression of alcoholic potency. Some of these ingredients that were use are: Cocculus indicus (violent poison that was used to stupefy fish), Opium, Indian Hemp, Strychnine, tobacco, darnel seed, logwood, and salts of zinc, lead, and alum.

- Less than 100 years after the birth of Porter, brown malt had already lost its place as the styles predominant grain.

What does the BJCP say about Porter?

12A. Brown Porter

Aroma: Malt aroma with mild roastiness should be evident, and may have a chocolaty quality. May also show some non-roasted malt character in support (caramelly, grainy, bready, nutty, toffee-like and/or sweet). English hop aroma moderate to none. Fruity esters moderate to none. Diacetyl low to none.

Appearance: Light brown to dark brown in color, often with ruby highlights when held up to light. Good clarity, although may approach being opaque. Moderate off-white to light tan head with good to fair retention.

Flavor: Malt flavor includes a mild to moderate roastiness (frequently with a chocolate character) and often a significant caramel, nutty, and/or toffee character. May have other secondary flavors such as coffee, licorice, biscuits or toast in support. Should not have a significant black malt character (acrid, burnt, or harsh roasted flavors), although small amounts may contribute a bitter chocolate complexity. English hop flavor moderate to none. Medium-low to medium hop bitterness will vary the balance from slightly malty to slightly bitter. Usually fairly well attenuated, although somewhat sweet versions exist. Diacetyl should be moderately low to none. Moderate to low fruity esters.

Mouthfeel: Medium-light to medium body. Moderately low to moderately high carbonation.

Overall Impression: A fairly substantial English dark ale with restrained roasty characteristics.

Comments: Differs from a robust porter in that it usually has softer, sweeter and more caramelly flavors, lower gravities, and usually less alcohol. More substance and roast than a brown ale. Higher in gravity than a dark mild. Some versions are fermented with lager yeast. Balance tends toward malt more than hops. Usually has an “English” character. Historical versions with Brettanomyces, sourness, or smokiness should be entered in the Specialty Beer category (23).

History: Originating in England, porter evolved from a blend of beers or gyles known as “Entire.” A precursor to stout. Said to have been favored by porters and other physical laborers.

Ingredients: English ingredients are most common. May contain several malts, including chocolate and/or other dark roasted malts and caramel-type malts. Historical versions would use a significant amount of brown malt. Usually does not contain large amounts of black patent malt or roasted barley. English hops are most common, but are usually subdued. London or Dublin-type water (moderate carbonate hardness) is traditional. English or Irish ale yeast, or occasionally lager yeast, is used. May contain a moderate amount of adjuncts (sugars, maize, molasses, treacle, etc.).

| Vital Statistics: | OG: 1.040 – 1.052 |

| IBUs: 18 – 35 | FG: 1.008 – 1.014 |

| SRM: 20 – 30 | ABV: 4 – 5.4% |

Commercial Examples: Fuller's London Porter, Samuel Smith Taddy Porter, Burton Bridge Burton Porter, RCH Old Slug Porter, Nethergate Old Growler Porter, Hambleton Nightmare Porter, Harvey’s Tom Paine Original Old Porter, Salopian Entire Butt English Porter, St. Peters Old-Style Porter, Shepherd Neame Original Porter, Flag Porter, Wasatch Polygamy Porter

12B. Robust Porter

Aroma: Roasty aroma (often with a lightly burnt, black malt character) should be noticeable and may be moderately strong. Optionally may also show some additional malt character in support (grainy, bready, toffee-like, caramelly, chocolate, coffee, rich, and/or sweet). Hop aroma low to high (US or UK varieties). Some American versions may be dry-hopped. Fruity esters are moderate to none. Diacetyl low to none.

Appearance: Medium brown to very dark brown, often with ruby- or garnet-like highlights. Can approach black in color. Clarity may be difficult to discern in such a dark beer, but when not opaque will be clear (particularly when held up to the light). Full, tan-colored head with moderately good head retention.

Flavor: Moderately strong malt flavor usually features a lightly burnt, black malt character (and sometimes chocolate and/or coffee flavors) with a bit of roasty dryness in the finish. Overall flavor may finish from dry to medium-sweet, depending on grist composition, hop bittering level, and attenuation. May have a sharp character from dark roasted grains, although should not be overly acrid, burnt or harsh. Medium to high bitterness, which can be accentuated by the roasted malt. Hop flavor can vary from low to moderately high (US or UK varieties, typically), and balances the roasted malt flavors. Diacetyl low to none. Fruity esters moderate to none.

Mouthfeel: Medium to medium-full body. Moderately low to moderately high carbonation. Stronger versions may have a slight alcohol warmth. May have a slight astringency from roasted grains, although this character should not be strong.

Overall Impression: A substantial, malty dark ale with a complex and flavorful roasty character.

Comments: Although a rather broad style open to brewer interpretation, it may be distinguished from Stout as lacking a strong roasted barley character. It differs from a brown porter in that a black patent or roasted grain character is usually present, and it can be stronger in alcohol. Roast intensity and malt flavors can also vary significantly. May or may not have a strong hop character, and may or may not have significant fermentation by-products; thus may seem to have an “American” or “English” character.

History: Stronger, hoppier and/or roastier version of porter designed as either a historical throwback or an American interpretation of the style. Traditional versions will have a more subtle hop character (often English), while modern versions may be considerably more aggressive. Both types are equally valid.

Ingredients: May contain several malts, prominently dark roasted malts and grains, which often include black patent malt (chocolate malt and/or roasted barley may also be used in some versions). Hops are used for bittering, flavor and/or aroma, and are frequently UK or US varieties. Water with moderate to high carbonate hardness is typical. Ale yeast can either be clean US versions or characterful English varieties.

| Vital Statistics: | OG: 1.048 – 1.065 |

| IBUs: 25 – 50 | FG: 1.012 – 1.016 |

| SRM: 22 – 35 | ABV: 4.8 – 6.5% |

Commercial Examples: Great Lakes Edmund Fitzgerald Porter, Meantime London Porter, Anchor Porter, Smuttynose Robust Porter, Sierra Nevada Porter, Deschutes Black Butte Porter, Boulevard Bully! Porter, Rogue Mocha Porter, Avery New World Porter, Bell’s Porter, Great Divide Saint Bridget’s Porter

12C. Baltic Porter

Aroma: Rich malty sweetness often containing caramel, toffee, nutty to deep toast, and/or licorice notes. Complex alcohol and ester profile of moderate strength, and reminiscent of plums, prunes, raisins, cherries or currants, occasionally with a vinous Port-like quality. Some darker malt character that is deep chocolate, coffee or molasses but never burnt. No hops. No sourness. Very smooth.

Appearance: Dark reddish copper to opaque dark brown (not black). Thick, persistent tan-colored head. Clear, although darker versions can be opaque.

Flavor: As with aroma, has a rich malty sweetness with a complex blend of deep malt, dried fruit esters, and alcohol. Has a prominent yet smooth schwarzbier-like roasted flavor that stops short of burnt. Mouth-filling and very smooth. Clean lager character; no diacetyl. Starts sweet but darker malt flavors quickly dominates and persists through finish. Just a touch dry with a hint of roast coffee or licorice in the finish. Malt can have a caramel, toffee, nutty, molasses and/or licorice complexity. Light hints of black currant and dark fruits. Medium-low to medium bitterness from malt and hops, just to provide balance. Hop flavor from slightly spicy hops (Lublin or Saaz types) ranges from none to medium-low.

Mouthfeel: Generally quite full-bodied and smooth, with a well-aged alcohol warmth (although the rarer lower gravity Carnegie-style versions will have a medium body and less warmth). Medium to medium-high carbonation, making it seem even more mouth-filling. Not heavy on the tongue due to carbonation level. Most versions are in the 7-8.5% ABV range.

Overall Impression: A Baltic Porter often has the malt flavors reminiscent of an English brown porter and the restrained roast of a schwarzbier, but with a higher OG and alcohol content than either. Very complex, with multi-layered flavors.

Comments: May also be described as an Imperial Porter, although heavily roasted or hopped versions should be entered as either Imperial Stouts (13F) or Specialty Beers (23).

History: Traditional beer from countries bordering the Baltic Sea. Derived from English porters but influenced by Russian Imperial Stouts.

Ingredients: Generally lager yeast (cold fermented if using ale yeast). Debittered chocolate or black malt. Munich or Vienna base malt. Continental hops. May contain crystal malts and/or adjuncts. Brown or amber malt common in historical recipes.

| Vital Statistics: | OG: 1.060 – 1.090 |

| IBUs: 20 – 40 | FG: 1.016 – 1.024 |

| SRM: 17 – 30 | ABV: 5.5 – 9.5% |

Commercial Examples: Sinebrychoff Porter (Finland), Okocim Porter (Poland), Zywiec Porter (Poland), Baltika #6 Porter (Russia), Carnegie Stark Porter (Sweden), Aldaris Porteris (Latvia), Utenos Porter (Lithuania), Stepan Razin Porter (Russia), Nøgne ø porter (Norway), Neuzeller Kloster-Bräu Neuzeller Porter (Germany), Southampton Imperial Baltic Porter

Wednesday, September 24, 2008

E300 in Czech Beer

http://www.praguemonitor.com

There have been a couple of comments about the widespread use of E300 in Czech beer, both here (in a comment from Max Bahnson on the post about Czech beer as a protected name) and from David over at Beer Oh Beer (where Max again casts his vote against it). Nothing more than ascorbic acid, also known as vitamin C, E300 is added as a preservative as well as to prevent the development of haze in beer.

I can understand people might want their favorite beverage to include no food additives whatsoever, but I also appreciate the use of vitamin C in my beer instead of, say, E211, also known as sodium benzoate, a preservative believed to potentially damage mitochondrial DNA, cause premature aging and possibly even cause Parkinson’s disease. (E300 it is!)

In fact, quite a few Czech beer labels show E300 on the back, including some of the very best — the one above is from Herold’s absolutely outstanding Bohemian Black Lager. But how much E300 are brewers allowed to put in your favorite bottle? The answer might surprise you.

Drumroll, please… According to EU regulations, there is no maximum amount of E300 that can be added to a beer. Nor is there any stated limit on any of the following:

E270, lactic acid

E301, sodium ascorbate

E330, citric acid

E414, acacia gum

For all of these E’s, the regulatory principle involved is one of quantum satis, meaning that there is no maximum specified. (The phrase can be parsed as “however much is needed.”) In regulatory terms, that might not be terribly reassuring. But in the case of vitamin C, it’s hard to imagine that even a high dosage would be anything other than beneficial.

Here’s a link for a PDF of Directive 95/2/EC, which regulated the amounts of food additives other than colors and sweeteners in the European Union.

Here’s a link for a PDF of Directive 2003/114/EC, which amends Directive 95/2/EC.

If you search through the documents, you’ll find that EU regulations also allow:

100 milligrams per liter of E405, propane-1, 2-diol alginate (propylene glycol alginate) in beer

1 gram per liter of E1520, propan-1, 2-diol (propylene glycol) in all beverages

200 milligrams per liter of E210 (benzoic acid), E211 (sodium benzoate), E212 (potassium benzoate) and E213 (calcium benzoate) in kegged alcohol-free beer

In addition, there are many weird E-numbers that are allowed to appear in all foodstuffs, not just beer. Go on, read it, but don’t open the file if you’re about to eat. It’s sure to put you off your lunch.

So if vitamin C is all we’re up against, I think I’m okay with it. I haven’t heard if ascorbic acid can affect the taste of beer, but I would imagine that it might contribute to the slight citric finish in some Czech brews, especially Czech dark lagers, which are hopped at much lower rates than Pilsner-style beers, and thus might need another natural preservative like ascorbic acid to stay good longer.

Here’s my final thought: vitamin C is an essential nutrient for life on earth. Many organisms synthesize it internally, though humans, of course, do not. It helps our bodies to neutralize free radicals. It helps protect our cells from oxidative stress. It helps our bodies absorb iron from food and is believed to reduce the risk of stroke. But more importantly: if a beer with a bit of added vitamin C can taste as good as Herold’s Bohemian Black Lager, how could it possibly be bad?

Monday, September 22, 2008

My Favorite Time of the Year

Well, it's my favorite time of the year again. The temperature is starting to drop a little bit, the sun is starting to set a little earlier, and the leaves are starting to change. As soon as I get the spirit of Autumn running through me I start to crave things like homemade apple cinnamon bread, pumpkin pie, maple syrup, apple cider.....and as of lately hard cider.

Well, it's my favorite time of the year again. The temperature is starting to drop a little bit, the sun is starting to set a little earlier, and the leaves are starting to change. As soon as I get the spirit of Autumn running through me I start to crave things like homemade apple cinnamon bread, pumpkin pie, maple syrup, apple cider.....and as of lately hard cider.As a homebrewer and someone who loves the fall, I thought it was kind of rediculous that I have never made an attempt at making hard cider. I've really enjoyed every example I've ever tried but I just never thought to give it a go. Do you see where this is going? Well I just got home from downstate because I had a wedding to go to this weekend so while we were down there we decided to go check out a cider mill. My family and I stayed in Howell, Michigan which is sort of in between Lansing and Ann Arbor. I'ts a beautiful area and we really had a lot of fun down there. We went to visit the Historic Parshallville Grist Mill near Fenton. It is a great place to bring your family. Well I picked up 5 gallons of their cider to use in my hard cider that I plan on doing in the next day or two. I'll post something on that later. I just wanted to let everyone know about this place and post some of my pics (Below)

Saturday, September 13, 2008

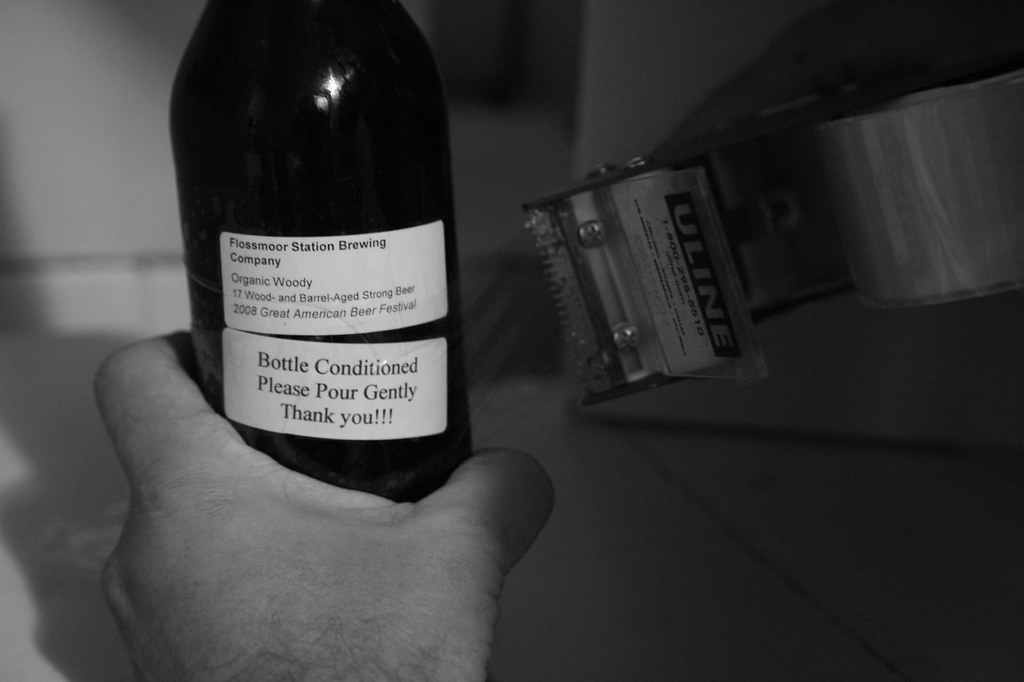

Biere Bella is off to the GABF

The GABF is coming up in October and my Biere Bella that Matt Van Wyk and I brewed this summer at Flossmoor Station Brewery is on its way to Colorado to be entered in the Pro Am competition. Keep your fingers crossed for us in hopes that we take home a medal.

Friday, September 12, 2008

All beers must have a starting gravity of at least 1.070. If you’re brewing “to style,” you have 24 categories to focus on:

These big beers need time to mature. That’s why we’re announcing the contest now and starting the judging in August! The contest will run for six months straight: August 2008 - January 2009. The first place beers from each month will go head-to-head to determine the Best of Show!

All beers will be judged by BJCP Certified Judges and score sheets will be sent for each beer entered.

PRIZES?

The beers that place 1st, 2nd & 3rd each month will be awarded a medal and a gift.

Each first place winner will receive:

•The latest brewing software from Beer Smith.

•Four ounces of hops, courtesy of Hop Union

BEST OF SHOW??? How’s this sound to you?

•8 Gallon Conical from Hobby Beverage

•$100 Gift Certificate from Northern Brewer (They are also offering a $50.00 Gift Certificate for 2nd place and a $25.00 Gift Certificate for 3rd Place)

•$50.00 Gift Certificate from Cap N Cork

•$50.00 Gift Certificate from Hopman’s

•The Beer Gun, from Blichmann Engineering

•5 gallon Ice Blanket & Insulated Sleeve from KEGlove

•Something from Hop Union (details to follow)

•Autographed copy of Brewing Classic Styles signed by Jamil Zainasheff and John Palmer

•Heavy-Duty Hoodie compliments of White Labs (2 place will receive a White Labs ball cap, 3rd - 5th place to receive White Labs yeast coupons

PLUS:

•The winning beer will be brewed at Kuhnhenn’s Brewery and put on tap at the pub

•The winner will also receive five gallons of this beer for themselves

•The winner will be allowed to brew this beer with the brewers themselves

•The winner will receive a $300 travel voucher if he (or she) doesn’t live within driving distance to Kuhnhen’s

There will be more details (and prizes) to be announced shortly, but since we’ve already mentioned some of the details on Episode 40, we figured we better start sharing what we know at this point.

Entry forms and contest rules are posted above. Just click to download either a Word doc or in PDF format.

What are you waiting for??? GET BREWING!!!

August Results:

1st Place: John McKissack’s Strong Ale with 41-point average (Vidor, TX)

2nd Place: Mike Krawszak’s Weizenbock with 34.5-point average (Royal Oak, MI)

3rd Place: Joe Vrabel’s Imperial ESB with 32.5-point average (Warren, MI)

Thursday, September 11, 2008

Brewing better beer: Scientists determine the genomic origins of lager yeasts

Print Article E-mail Article

Close Window ]Contact: Peggy Calicchiacalicchi@cshl.edu516-422-4012Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

Brewing better beer: Scientists determine the genomic origins of lager yeasts

Yeast, the essential microorganism for fermentation in the brewing of beer, converts carbohydrates into alcohol and other products that influence appearance, aroma, and taste. In a study published online today in Genome Research (www.genome.org), researchers have identified the genomic origins of the lager yeast Saccharomyces pastorianus, which could help brewers to better control the brewing process.

For thousands of years, ale-type beers have been brewed with Saccharomyces cerevisiae (brewer's or baker's yeast). In contrast, lager beer, which utilizes fermentations carried out at much lower temperature than for ale, is a more recently developed alcoholic beverage, appearing in Bavaria near the end of the Middle Ages. Lager beer gained worldwide popularity starting in the late 1800s, when the advent of refrigeration made year-round low-temperature fermentations possible. Saccharomyces pastorianus, the yeast used in lager brewing, is a "hybrid" organism of two yeast species, Saccharomyces bayanus and S. cerevisiae. It is thought that the contributions of both parent species resulted in an organism able to out-compete other yeasts during the cold lager fermentations.

Though early brewers understood that different brewing conditions would produce a unique beer, scientists are now unlocking the genetic differences between yeast strains that produce variation in flavor, color, and aroma. By comparing the genomic properties of yeast strains sampled from breweries around the world, Drs. Barbara Dunn and Gavin Sherlock of Stanford University have measured the genetic contribution of the parent yeasts to strains of S. pastorianus and revealed new insights into the events that brought about the evolution of lager yeast.

Surprisingly, the researchers found evidence that S. pastorianus strains used by brewers today may not have arisen from a single hybridization event, as was previously believed. "There were two independent origins of today's extant S. pastorianus strains," said Sherlock. "It is likely that each of these groups derived the S. cerevisiae portions of their genomes from distinct but related ale yeasts, and that these natural hybrids were then selected by brewers due to their abilities to ferment at cold temperatures."

While this work identified two distinct groups of S. pastorianus, Sherlock noted that they observed significant genetic variation and flexibility within the groups as well. Dunn and Sherlock speculated this genomic flexibility could have implications for the unique properties of each brewer's beer. "The fact that lager yeasts isolated from different breweries each seem to have a unique genomic make-up may indicate that the yeasts are adapting to the conditions specific to each brewery," explained Dunn.

Furthermore, this work paves the way for the characterization of specific genetic features of each strain that could aid in the brewing process. "Our discovery that unique genomic structures may be characteristic to each brewery and/or beer type could lead to insights on how to directly control flavor and aroma in beer," said Dunn.

###

Scientists from Stanford University (Stanford, CA) contributed to this study.

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health.

Media contacts:

Gavin Sherlock, Ph.D. (sherlock@genome.stanford.edu; +1-650-498-6012) has agreed to be contacted for more information.

Interested reporters may obtain copies of the manuscript from Peggy Calicchia, Editorial Secretary, Genome Research (calicchi@cshl.edu; +1-516-422-4012).

About the article:

The manuscript will be published online ahead of print on September 11, 2008. Its full citation is as follows: Dunn, B., and Sherlock, G. Reconstruction of the genome origins and evolution of the hybrid lager yeast Saccharomyces pastorianus. Genome Res. doi:10.1101/gr.076075.108.

About Genome Research:

Genome Research (www.genome.org) is an international, continuously published, peer-reviewed journal published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. Launched in 1995, it is one of the five most highly cited primary research journals in genetics and genomics.

About Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press:

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press is an internationally renowned publisher of books, journals, and electronic media, located on Long Island, New York. It is a division of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, an innovator in life science research and the education of scientists, students, and the public. For more information, visit www.cshlpress.com.

Genome Research issues press releases to highlight significant research studies that are published in the journal.

Wednesday, September 10, 2008

Making beer-main types of beer

Monday, September 8, 2008

Red Haven Peach Berliner Weisse

Well, I guess I shouldn't call it a Berliner Weisse. I had brewed a Berliner Weisse some time ago and it has completey fermented all the way out and it is still not nearly as sour as I would like it to be. I've been just sitting on it trying to figure out what to do with it. My friend piped in one night with an idea to throw a bunch of fruit on it to give the bugs some more sugar to work on. Sounded like a great idea to me. Well about a week ago me and the family were on the way home from the De Young Family Zoo in Wallace, MI and we drove by a bunch of fruit stands, one of which had a big sign that said "Red Haven Peaches". Me and my wife both looked at each other and said "Go Back". So I turned around and bought a half bushel of peaches for $17.00. A pretty good deal I thought. After I got them home I cleaned them up really good and removed all of the pits. I filled three big freezer bags full of my clean peaches and froze them. I got exactly 5 lbs in each bag and I through away all of the peaches that I thought didn't look that great. I also ate a few of course. Before adding them to my beer I let them though out and then ran them all through a food processor. I then added them to a large stock pot and brought them up to 160F for about a half hour and also added some pectic enzyme. Once they cooled down I racked my beer onto the peaches (10 lbs worth) and I also added a vile of White Labs Brett Bruxellensis that I have been holding onto for a while now. It was just passed expiration so I figured I'd just pitch it in here since there is a host of bugs already at work. It didn't show much activity the first few days but now I am starting to see some action in the air lock and the pellicle has kicked back up quite a bit.

Sunday, September 7, 2008

Maple Milk Stout

Jasper's Pure Maple Syrup

jaspermaple.com My Brewin' Buddy

So in my last post I mentioned I was roasting some brown malt that I was planning on using in a milk stout that I was going to do using maple syrup and roasted pecans. I brewed up my stout this weekend but I did not use the pecans. I'm still going to do a beer with them I think but the main reason I was planning on doing this stout was to grow up enough yeast to make a Russian Imperial Stout and I didn't know if the fats in the pecans would have the same effect on yeast that excessive amounts of hops can have. If you brew a beer with a lot of hops and try to reuse the yeast the results can be less than ideal because the oils can coat the yeast cell walls inhibiting optimal performance. So I brewed my stout without the nuts but I still think it is going to taste great. The though of blending in a touch of Frangelico at bottling has crossed my mind. Not sure if I'll do it. I'll probably try a small sample and see how it tastes. Here is the recipe I used:

Maple Milk Stout (5.5 gal batch)

Grain

4.25 lb Maris Otter

2 lb American Pale

2 lb Brown Malt (see prev post on how)

1 lb Black Patent

1 lb Honey Malt

2 lb Maple Syrup (Jasper's Maple Syrup from da U.P.)

1 lb Lactose

Hops

E.K. Goldings (31 IBUs) 60 min

Mashed at 155-156F for 60 min

Mashed out at 168F

O.G. 1.069

WlP 001 Cal Ale yeast

fermenting at 67-68F

Wednesday, September 3, 2008

Making Brown Malt

(click on pic to see it up close and personal)

This picture above is the color when it is done. At least mine was. I read that I should pull it out of the oven when I think it smells right rather then when it looks right. It smelled pretty damn good when I pulled it out.

Untoasted 2-row

Getting Ready To Go In The Oven at 225F

225F for 30 Min to dry it out completely.

Then:

30 Min at 300F

30 Min at 350F

Once you hit 350F make sure you

take the grain out and turn it over every 5-10

min. or so so it doesn't get burned.

This is what I ended up with

I'm sitting at my kitchen table right now drinking a 750ml of Trois Pistoles and enjoying the incredible smell coming from this pumpkin candle my wife bought and the aroma of 2row toasting in my oven at 350 F. I have to say, all of a sudden I am craving autumn and it's rich air and cooler temperatures. I decided to try and make my own brown malt tonight because I am planning on brewing up a stout that is basically going to be a beefed up milk stout with pecans and maple syrup and probably some cinnamon just before bottling. I wanted to use some brown malt in this to add that nice touch of fall. (gotta go turn my grain.....)

Wow, I opened my oven and you'd of thought I was making butterfingers. My whole house smells like a combination of toasted pumpkin seeds, popcorn, butterfinger candy bars, and chocolate. The smell alone is reason enough to toast your own malt. It is starting to turn a nice light brown. I started my toasting it at 225F for 30 minutes just to dry it out completely, the I gave it 30 min at 300F. I've stepped it up to 350F (the temp brown malt was traditionally roasted at albeit over a wood fire and rapidly brought up to temp) and now it is starting to definitely change in color. I've been turning it every 10 min or so now that I am at 350F as not to burn it.

That's what I did to get my brown malt. After reading Randy Mosher's book "Radical Brewing" I saw that he had this chart, which is pretty close to what I did. I just started at lower temps and worked my way up instead of just starting at your desired temp. I must state that I also dry roasted my grains giving it a toastier flavor rather then moistening my grain and then roasting them which would have given it a richer, more caramelized toast.

Min F (C) Color (L) Flavor

20 250 (121) Pale Gold (100) Nutty, not toasty

25 300 (149) Gold (20) Malty, Carmelly, rich, not toasty

30 350 (177) Amber (35) Nutty, Malty, Lightly Toasted

40 375 (191) Deep Amber (65) Nutty, toffee-like, crisp toastiness

30 400 (204) Copper (100) Strong toasted flavor, some nutlike notes

40 400 (204) Deep Copper (125) Roasted, not toasted, like porter or coffee

50 400 (204) Brown (175) Strong Roasted flavor

Tuesday, September 2, 2008

Monday, September 1, 2008

Brew Bubbas Radio

Thanks to Craig & Jerry for having me on. I really enjoyed it.

Brew Bubbas Radio

Michigan State Fair Homebrew Competition Wrap-Up

See all the results here